معهد الهقار متخصص في البحوث حول البلدان المغاربية، مهمته المساهمة في تعميق الفهم للمشاكل المتعددة التي تواجهها الشعوب المغاربية وكذا التعريف بجهودهم وأفكارهم من أجل تحسين أوضاعهم.

كما يقوم معهد الهقار بنشر وتوزيع كتب ذات نوعية عالية وجذابة وفي متناول الجميع. إضافة إلى ذلك ينظم معهد الهقار دورات دراسية ومنتديات من أجل تنقل وتبادل الأفكار

Hoggar is a research institute with a particular focus on the Maghreb.

Hoggar‘s mission is to contribute towards a deeper understanding of the multi-faceted problems facing the peoples of the Maghreb, and to give voice to their struggles and creative ideas to better their conditions.

Hoggar is committed to publishing and distributing high quality, attractive and affordable books.

Hoggar also pursues its mission by organising workshops, seminars and conferences.

Hoggar est un institut de recherche sur le Maghreb.

Hoggar se donne pour mission de contribuer à approfondir la compréhension des problèmes multi-dimensionnels des peuples du Maghreb et à faire entendre leurs luttes et leurs idées novatrices pour améliorer leurs conditions.

Hoggar publie et distribue des livres de haute qualité, attrayants et abordables.

Hoggar organise des sessions de formation et des forums pour la circulation et l’échange des idées.

|

Que signifie Hoggar ?

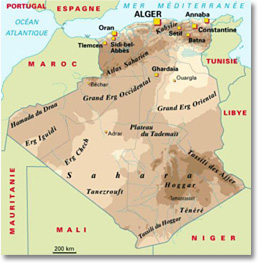

Le nom de notre institut tient des massifs volcaniques qui s’élèvent en pente raide du fond de la partie nord et centrale du désert du Sahara. Le Hoggar est aussi appelé Ahaggar. |

|

The Hoggar in a few words The Hoggar Massif lies in the north-central part of the Sahara desert. The Sahara (from the Arabic word sahra which means wilderness) is a 7 million kilometer square desert bounded by the Atlas mountains and the Mediterranean Sea on the north, Egypt and the Red Sea on the east, the Sudan and the valley of Niger River on the south, and the Atlantic Ocean on the west. The Sahara has a central mountainous system which includes the Tibesti Massif in Chad, the Air Mountains in Niger, and the Hoggar Massif in Algeria.

The Hoggar has a mean altitude of about 900 meters above sea level, its highest point being the Tahat mount (3003 meters). It comprises a series of plateaus, such as the Tassili Immidir or the Tassili N’Ajjer etc. (tassili means plateau), as shown in the map. The Hoggar has a mean altitude of about 900 meters above sea level, its highest point being the Tahat mount (3003 meters). It comprises a series of plateaus, such as the Tassili Immidir or the Tassili N’Ajjer etc. (tassili means plateau), as shown in the map.The physical features of the Hoggar are varied. For instance, the Atakor area is made up of hundreds of towering organ-pipes looking monoliths composed of volcanic rock; the indigenous nomads (the tuareg) call this region the assekrem (‘the end of the world’). The Tassili N’Ajjer looks like a series of steep-sided valleys, shaped by lake and river fluvial action for thousands of year; some plateaus are strewn with ‘stone forests’, rock formations resulting from sand-laden wind erosion.

Very little rain falls on the Hoggar (mean annual rainfall is about 30 mm), but there are subterranean sources of water. The temperature range is extreme, extending from freezing to more than 54 C (130 F).

Humid micro-climates have allowed the preservation of a few flora species. The Hoggar and Tassili mountains host cypress, wild olive and myrtle flora elements, which grow at the bottom of wadis, beside gueltas, travertine dams, or waterfalls. The fauna contains a large number of spiders, insects, reptiles, Tilapia fish, and mammals such as Barbary sheep, Dorcas gazelles, Roan antilopes, caracal, and cheetah. The last crocodiles were killed in the 1940s in the Oued Imirhou. Migratory palaearctic birds also use the Hoggar as a resting station (golden eagles, herons, white storks etc.). The Hoggar is a site of a rich cultural heritage. The Tassili N’ajjer has been classified as a Natural World Heritage Property by Unesco. Its pre-historic remains comprise rock engravings of man and large fauna (elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus ), rock paintings of the same, stone monuments, neolithic remains from the 6000 to 2000 BC period such as pottery, grinding instruments, enclosure walls, sculptures etc. There are series of ancient cave paintings some of which are arranged in chronological sequence. These depict stylised figures, dancers, scenes of weddings, banquets, pastoral life, moufflon hunting, chariots, etc., and inscriptions in Tifinagh characters, an alphabet that is used by the Tuareg to this day. Altogether, it is estimated there are about 15000 drawings and engravings representing the evolution of human life, climatic changes and animal migrations from 7500 BC to the first centuries of the present era. The indigenous inhabitants of the Hoggar are the Tuareg (plural of Targui – also known as Kel Tamachek or blue men of the desert). The nomadic and sedentary Tuareg are a proud and freedom-loving people. Traditionally, the Tuareg were organised politically under a confederation set-up involving the Hoggar, N’Ajjer, Tadamakat, Udalan, Adagh and the Aïr. French colonialism dismantled this confederation despite a fierce resistance which earned the Tuareg a reputation of indestructibility in the eyes of the French military. This state of affairs was perpetuated even after the French lost North Africa as the Tuareg were kept divided between the political borders of Algeria, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso, Nigeria and Lybia. This partition has provoked the falling apart of families and the weakening of Tuareg society and culture. The Tuareg are also experiencing a marginalisation, and denials of their social, political, and cultural rights in all these nation states. But the most ominous persecution of the Tuareg has been the recent genocidal massacres of several thousands of Tuareg in Niger (Tchin-Tabaraden in May 1990) and Mali (Foita, Gao, Gossi, Goundam, Kidal, Lere, Menaka, and Timbuktu between 1990 and 1994), prompting mass exodus and waves of refugees into Algeria and Mauretania, some of whom died from epidemics, starvation and cold. The Tuareg are a Muslim people and have a unity of language, known as Tamajaq or Tamashaq , which is a Berber dialect. The social structure of the Tuareg has a central fault-line between the Ihaggaren or Amaher (noble classes) and Imghad (serf classes). Women have powerful influence in family affairs and social life. The Tuareg have had queens as rulers (called Tamenokalt – the most famous was Tin Hinan whom they regard as ‘our mother’ to the present day). Tuareg women are well renowned for their poetry. Historically, the Tuareg played the role of bridge between the North and the West of Africa. The Tuareg are suffering to this day from the loss of this historical capacity and position, dismantled by French colonialism, and perpetuated since by voracious military regimes in the name of exclusivist and smothering notions of nation-state. They are a people struggling to re-invent a better future. In the words of a Targui woman: ‘I want only to wander freely in my country, only in my country. I want to be a taxi of freedom, which is guided and led solely by the wind of freedom. Through the freedom of the air, I want to criss-cross the country, to go from east to west, from south to north, just like the wind of freedom. But to become a taxi of freedom in the desert of my country, there are many steps and struggles ahead to get back our truth.’ |